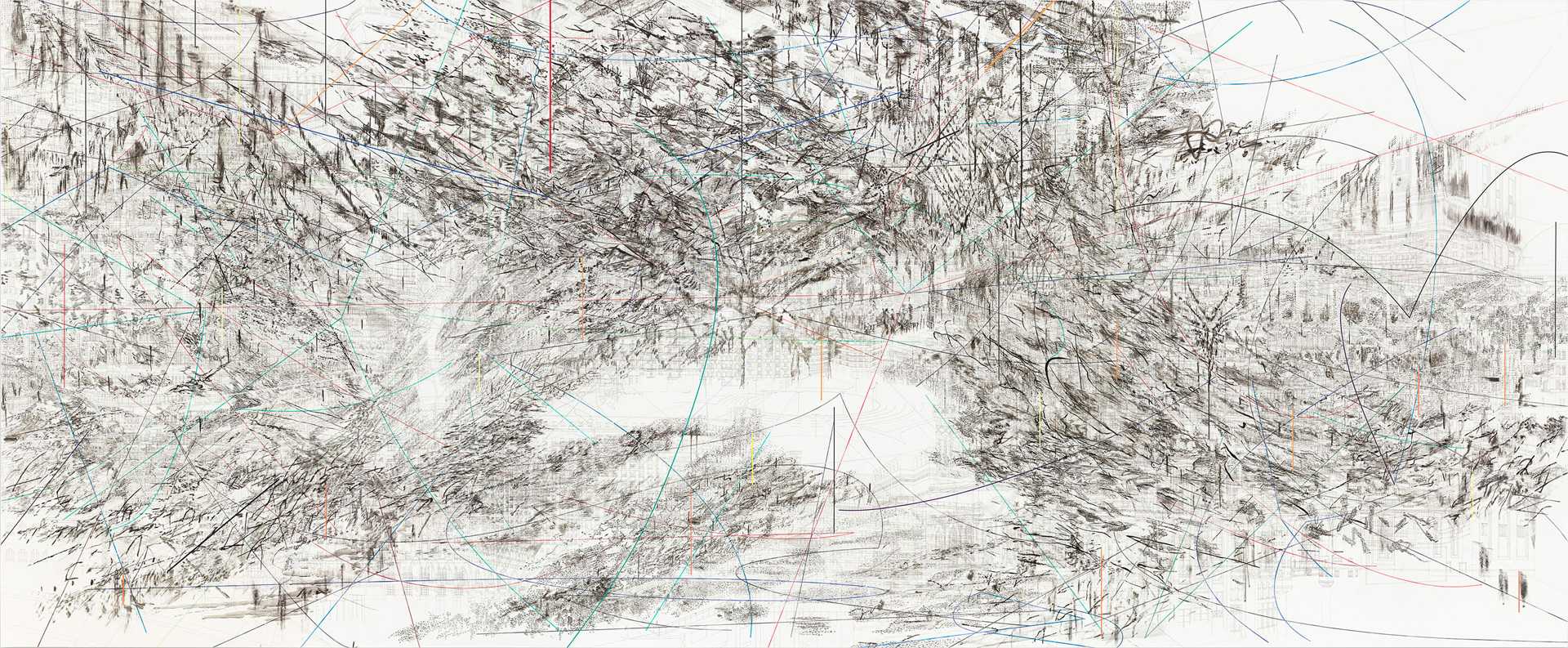

Cairo

In her monumental paintings, Julie Mehretu begins with controlled public spaces, using elements of mapping and architectural drawing to create dense landscapes. Cairo presents the ancient Egyptian city caught in a furious wind blowing off the Sahara, its structures and history extending into vectors. Simultaneously, the work portrays Cairo as the contemporary, revolutionary city in the political spotlight as the seat of the Arab Spring, raising the world’s consciousness about government suppression and citizen-led change. In the middle of the work is a rendering of Tahrir Square, the site of several historical protests, which came to symbolize democracy during the 2011 uprisings. Mehretu’s version is stripped down to the most basic details: an oblique circle denoting the grassy center surrounded by light posts and concentric traffic lanes. The painting is devoid of people, so landmarks and cityscapes stand in for collective actions as locations of both past events and potential future resistance.

Born in Ethiopia in 1970, Julie Mehretu was raised in East Lansing, Michigan. Since 1999, she has lived and worked in New York, establishing herself as one of the most exciting painters in the United States. Like other artists in The Broad collection, including Franz Ackermann, Matthew Ritchie, and Mark Bradford, Mehretu mines the history of abstract expressionism. Using its all-over compositions and networked lines and webs, she considers contemporary life, from the sprawling growth of cities to the exponential expansion of information in the digital age. Mehretu’s work features multiple layers of visual texture, alternating between drawing and painting to build up great density and depth.

Mehretu produces her works much in the way a city gathers its memories. She starts each painting with a geometric structure that serves as the basic anchor and organization for the image. From that point on, Mehretu’s method is intuitive: she adds and subtracts images and drawings according to how she envisions the painting’s resolution. These actions are the literal history of Mehretu’s process—some marks exist in the completed work, other marks appear only as ghosts or memories that have partially disappeared. The highly worked finished piece acts as a timeline of weather and events, as if it is the unexpected result of the original geometry, the outcome of something that did not quite go according to plan.

Cairo, 2013, portrays the ancient Egyptian city caught in a furious wind blowing off the Sahara, its structures and history surging and extending into multiple vectors of black-and-white drawing. At ten feet tall and twenty-four feet in length, the immense work registers as a physical force, asserting itself as a unified mass. However, the concomitant detailing, the obvious care shown to each individual moment on the canvas, allows for lush viewing over a long period of time. Mehretu’s Cairo is more than a map, more than a picture; it is an attempt to express a city’s life, its mixed forces, and the full complication of its continued existence.