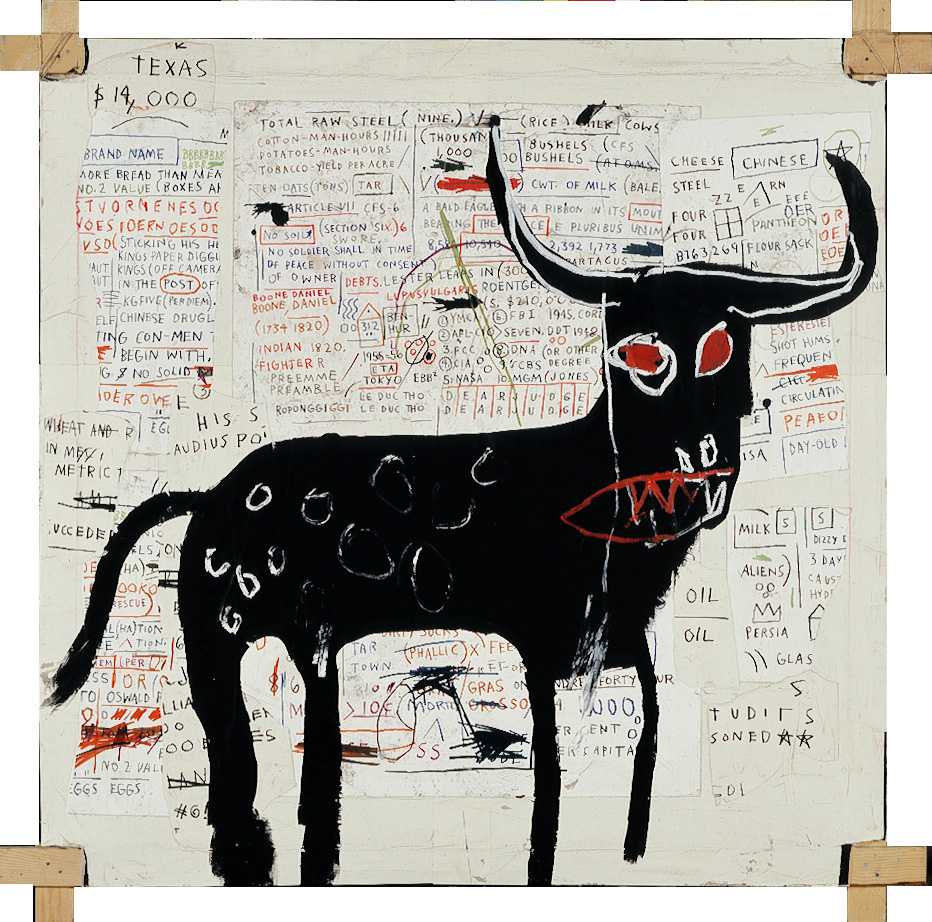

Beef Ribs Longhorn

My name is Thomas Houseago.

Beef Ribs Longhorn, by Jean‐Michel Basquiat from 1982. You know, America in the '80s, it's pop, and he's coming from a world of graffiti, of street art that is in some ways reacting to and starting to break down the hard-edged removal of the hand, removal of the person that pop had become. That it was printing, it was mass reproduction, it was MTV, it was advertising. In a way, Basquiat is part of a generation that's, again, resisting this, and playing with it in a different way that, say, Andy Warhol did, then went to Jeff Koons, and went to this side where its heart is pop. Its heart is the mass reproduction. Its heart is the machine-made image. Basquiat is twisting and turning that. He's bending it. He's showing its human soul in a way.

This language of pop, this language of graffiti, this language of street culture that has been taken and turned into a selling point, or its own kind of industry in a way, this painting stands as a warning against that, as a refusal, again, to enter a simplistic reading of where the figure is, or where the reading of how we are as humans, how we're dealing with our world, it doesn't sit comfortably. You start to look at this longhorn livestock, and suddenly it's this monstrous image of this animal, and this almost sick, almost terrifying dream, that nightmarish vision. It's a beast, and a demon, and an animal, and a human without a doubt. These things get jumbled and pulled together.

Still, it is a stand-in. It is a really terrifying ... Within it is this huge complexity of livestock, of something being born, of something being doomed. You feel it in that piece, but you also feel there's something demonic about that creature, that it will have its revenge somehow, right?

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn to Haitian and Puerto Rican parents in 1960, and left home as a teenager to live in Lower Manhattan, playing in a noise band, painting, and supporting himself with odd jobs. In the late 1970s, he and Al Diaz became known for their graffiti, a series of cryptic statements, such as “Playing Art with Daddy’s Money” and “9 to 5 Clone,” tagged SAMO. In 1980, after a group of artists from the punk and graffiti underground held the “Times Square Show,” Basquiat’s paintings began to attract attention from the art world.

In the 1981 article “The Radiant Child,” which helped catapult Basquiat to fame, critic Rene Ricard wrote, “We are no longer collecting art we are buying individuals. This is no piece by Samo. This is a piece of Samo.” This statement captures the market-driven ethos of the 1980s art boom that coincided with polarizing views played out in government and media, known as the culture wars. In this context, Basquiat was keenly aware of the racism frequently embedded in his reception, whether it took the form of positive or negative stereotypes. In his work, he integrated critique of an art world that both celebrated and tokenized him. Basquiat saw his own status in this small circle of collectors, dealers, and writers connected to an American history rife with exclusion, invisibility, and paternalism, and he often used his work to directly call out these injustices and hypocrisies.

Before his tragic death in 1988 at the age of twenty-seven, Basquiat expressed seemingly boundless creative energy, producing approximately a thousand paintings and two thousand drawings. Over the decades, the study of Basquiat’s paintings and drawings has offered textured insights of the 1980s and, importantly, continued reflections on Black experience against an American and global backdrop of the white supremacist legacy of slavery and colonialism. At the same time, Basquiat’s work celebrates histories of Black art, music, and poetry, as well as religious and everyday traditions of Black life.

Many of Basquiat’s works have been likened to the improvisational and expansive compositions of jazz. Often themes accumulate through multiple references on the surface, emerging as patterns out of gestural brushstrokes, symbols, inventories, lists, and diagrams. Most images in Basquiat’s works have double and triple meanings, some of which the artist discussed and others that he left undefined, remaining open to viewers’ interpretations. Basquiat sought and enjoyed unlikely collisions of imagery and words, massive influxes of information and stimuli that recreated the experience of being in a world by turns exciting, inspiring, oppressive, and toxic.