Untitled

This untitled work, sometimes known as ‘Skull’ by Jean-Michel Basquiat is likely to be inspired by a key moment from his childhood.

When Jean-Michel was a boy, around seven or eight, [SOUNDFX: car screeching to a stop] he was hit by a car and broke his arm.

To help him pass the time during his recovery, his mother brought him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, a medical textbook with illustrations and diagrams of the human body.

Jean-Michel’s mom was from Puerto Rico and his dad was from Port Au Prince in Haiti - a country in the Caribbean that practices a religion called Vodou. Skulls are a common image in Vodou, and are mostly seen as symbols of death.

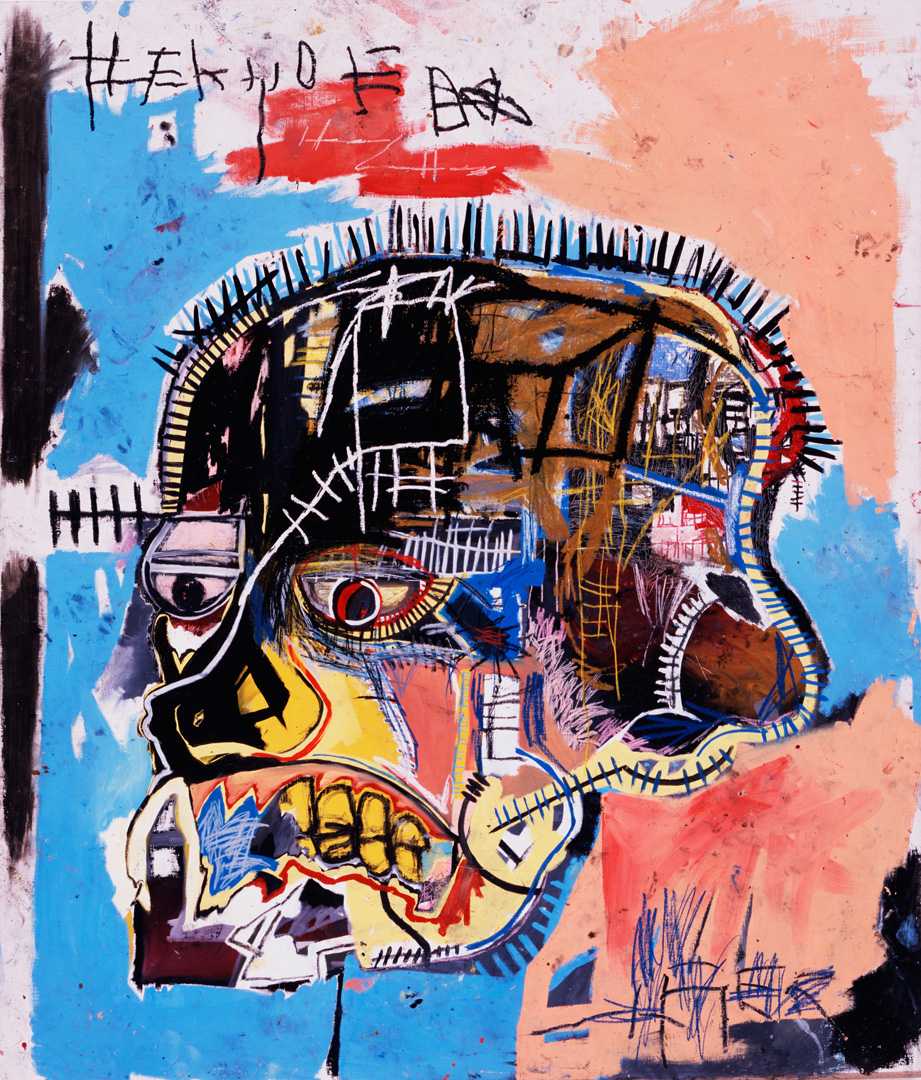

Because we are able to see [SOUNDFX: teeth and jaw clattering] teeth and jaw in this painting, we might think of it as a skull, but we can see eyes, a nose and an ear, and grass-like hair growing. And inside where the brain should be are different, connected room-like spaces in a variety of colors.

It’s like we can see the inside and outside of this “skull” at once.

It’s a skull that’s both very alive; yet dead.

I think it’s more like a head.

Many of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s paintings are in some way autobiographical, and Untitled may be considered a form of self-portraiture. The skull here exists somewhere between life and death. The eyes are listless, the face is sunken in, and the head looks lobotomized and subdued. Yet there are wild colors and spirited marks that suggest a surfeit of internal activity. Developing his own personal iconography, in this early work Basquiat both alludes to modernist appropriation of African masks and employs the mask as a means of exploring identity. Basquiat labored over this painting for months — evident in the worked surface and imagery — while most of his pieces were completed with bursts of energy over just a few days. The intensity of the painting, which was presented at his debut solo gallery exhibition in New York City, may also represent Basquiat’s anxieties surrounding the pressures of becoming a commercially successful artist

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn to Haitian and Puerto Rican parents in 1960, and left home as a teenager to live in Lower Manhattan, playing in a noise band, painting, and supporting himself with odd jobs. In the late 1970s, he and Al Diaz became known for their graffiti, a series of cryptic statements, such as “Playing Art with Daddy’s Money” and “9 to 5 Clone,” tagged SAMO. In 1980, after a group of artists from the punk and graffiti underground held the “Times Square Show,” Basquiat’s paintings began to attract attention from the art world.

In the 1981 article “The Radiant Child,” which helped catapult Basquiat to fame, critic Rene Ricard wrote, “We are no longer collecting art we are buying individuals. This is no piece by Samo. This is a piece of Samo.” This statement captures the market-driven ethos of the 1980s art boom that coincided with polarizing views played out in government and media, known as the culture wars. In this context, Basquiat was keenly aware of the racism frequently embedded in his reception, whether it took the form of positive or negative stereotypes. In his work, he integrated critique of an art world that both celebrated and tokenized him. Basquiat saw his own status in this small circle of collectors, dealers, and writers connected to an American history rife with exclusion, invisibility, and paternalism, and he often used his work to directly call out these injustices and hypocrisies.

Before his tragic death in 1988 at the age of twenty-seven, Basquiat expressed seemingly boundless creative energy, producing approximately a thousand paintings and two thousand drawings. Over the decades, the study of Basquiat’s paintings and drawings has offered textured insights of the 1980s and, importantly, continued reflections on Black experience against an American and global backdrop of the white supremacist legacy of slavery and colonialism. At the same time, Basquiat’s work celebrates histories of Black art, music, and poetry, as well as religious and everyday traditions of Black life.

Many of Basquiat’s works have been likened to the improvisational and expansive compositions of jazz. Often themes accumulate through multiple references on the surface, emerging as patterns out of gestural brushstrokes, symbols, inventories, lists, and diagrams. Most images in Basquiat’s works have double and triple meanings, some of which the artist discussed and others that he left undefined, remaining open to viewers’ interpretations. Basquiat sought and enjoyed unlikely collisions of imagery and words, massive influxes of information and stimuli that recreated the experience of being in a world by turns exciting, inspiring, oppressive, and toxic.